The Murchison Experiment: Tech Fasting and Finding Community at St John’s Santa Fe

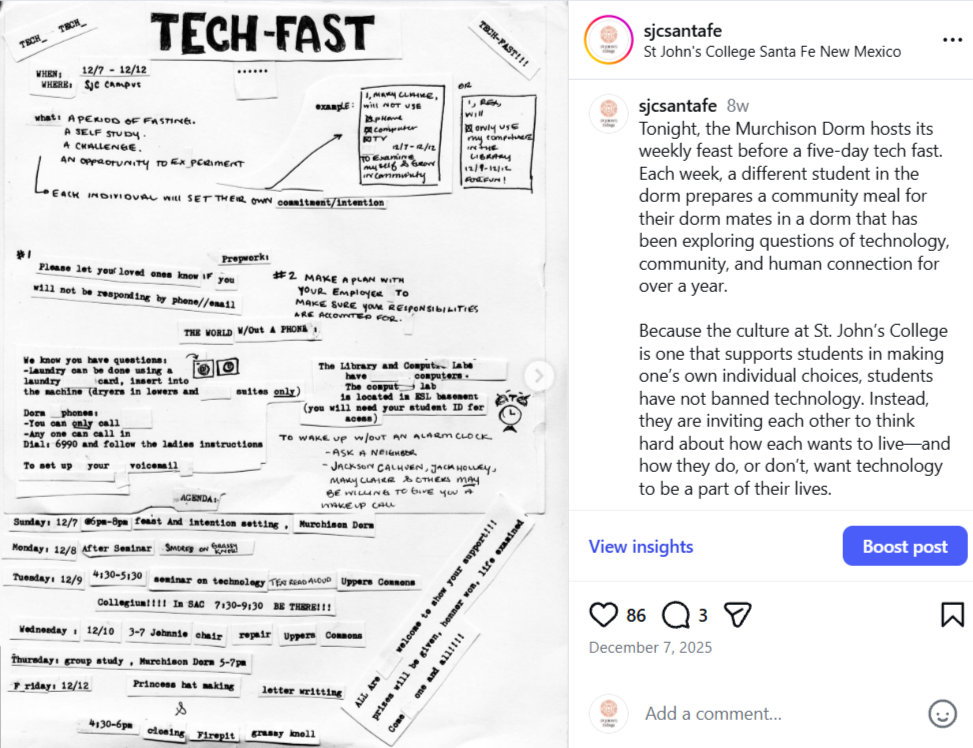

On January 3, 2026 an article appeared in the New York Times highlighting a Tech Fast community leadership project I facilitated with students in my residence hall. While this social experiment has, sweetly, captured national attention, this was not the first time I experimented with community building and social change.

I am an RA in Murchison Hall, a rather standard dorm in its construction, and although I believe that all my residents (“dormies”) are truly exceptional, they are a pretty standard bunch of geniuses that attend St. John’s Santa Fe. I am writing this in year two of what is now called the “Murchison experiment”. It began with a group of interested people wanting to live “screen free” and has evolved very naturally into a group of people interested in wanting to live closer together by any means whatsoever. Over the past year we have focused on fortnightly dorm meals (every two weeks), living comfortably in community, and supporting whatever other projects bubble up from the group. We have performed a cabaret, hosted many meals, tea parties and game nights, waltzed in the hallways, thrown a disco rave, and recorded a scene from Antigone.

We had initially asked for one or two suites in the newly built dorms, which come with kitchens and living rooms, perfect for our evolving communal, compost forward, group of students. This request was raised in a student government meeting, but we were understandably denied because of the need for ADA accommodations and single gender dorm spaces. However, intentional community and low tech living were important to us, and we would not wait for the perfect conditions to manifest it.

Sometimes I hear people asking for solutions or mulling over what might possibly fix this beautiful world they claim is broken, and it is important to recognize that sometimes solutions will not be beautiful or easily explained, but that people have gathered forever, and we can continue to do so whenever we like. To begin gathering in the community we must begin, and there seems to be a difficulty that sometimes obscures that simplicity. Instead, we started putting furniture in the hallways and asked people to gather and eat together on the stairs.

One thing I have loved about working with the other Endeavor Fellows is their approach to evidence-based solution seeking. They combine a Western need for numbers and proof with intuitive understandings of community building and healing. By this I mean: we quest for evidence that spending more time outside helps well-being, of course stepping away from addictive technologies helps, and of course, using one’s hands as tools are beneficial to mental well-being. And, at times it feels absurd to require proof for what seems obvious. Perhaps more importantly, having the backing of and discussions in the Student Fellows group and ELC in general has gifted me with another push, another vote of confidence, to support the initiatives I have been contemplating for some time.

Through the Endeavor Fellows work, we learned about Johnathan Haidt’s book, The Anxious Generation, in which Dr. Haidt calls attention to the impact of addictive technologies and social media (often perveyed through cell phones) on youth mental health. While there seems to be ample evidence that shows our relationship with computers, phones and televisions impacts our personal well-being, we lack a sense of where to start or how to push against “what is”. During the tech fast, one of my tutors argued, “We must not be in resistance to the world as it is,” as though I were resisting reality rather than actively manipulating it to the best of my abilities. While Dr. Haidt offers numerous proposals and policy options for transforming the system, I am not asking to live in a world without phones forever. I wanted only to witness, and facilitate the witnessing, of how addictive technologies have become necessitated by the powers that be, and what our modern world could look like if we refused them, even for a short period.

Over the week of December 7-12, 2025, Murchison took on the community challenge of a tech fast, several observations emerged across our shared experience. I rediscovered the joys that can fill moments of boredom. Orange juice was savored. Plans had to be made—and kept. I felt the need for my projects to be visible, even in courtyards, just to attract passersby. I found my way to a soap and supply store by checking every street between the Jiffy Lube and the Dutch Bros. A dear friend learned about extreme flooding in her hometown through the grapevine. I bought the wrong plane tickets on a library computer. I didn’t feel guilty about my texts, Teams messages, or emails piling up. Other “fasters” said they enjoyed listening to Bach on their car radios like never before. Some found a solidity in their daily actions because no other technological options were brewing in the background. The fast functioned truly as an observance, one that allowed people to witness their everyday lives within a new context.

We discovered how technology is insidiously built into the very systems of our daily existence. Ironically, we do not even have photos to share during this experiment because my phone is my camera. I failed to find a midnight vigil because I did not use my GPS. We could not communicate via a simple text if we were going to be late or were uncertain where to meet. Our school was unsure how to communicate with us (without the confidence in our mass text system) in case of an emergency. We could not do laundry without the ability to scan a payment system, and we had to work with our teachers to get assignments, normally assumed accessible through our learning management system. Some found it harder to wake up without their phone (who owns an alarm clock?) but easier to fall asleep. We appreciate the challenges and the insights garnered from the Fast.

Technology and phones pose challenges to our daily living and community building at the same time that they are tools for navigating our world. At St. John’s, there is an ongoing discussion about separating students from addictive technology while simultaneously requiring the very same tools to function. Assuming technology in and of itself is not the problem, perhaps a period of fasting can better illuminate, for each of us, the ways they are tools and the ways in which they are harmful, and assist us in our conversations about their regulation or required use with more open and informed eyes. This is why I believed there could be power in a short demonstration to explore the pervasiveness of technology and the question of how to find mental health and clarity in a world with it at the center.

As a result of this experiment, we discovered how deeply embedded and addictive technologies are in our lives but, arguably more importantly, we were finally able to see what efforts would be required of us to choose to live differently. We were required to practice being accountable and proactive in our scheduling, forgiving toward our friends, and reflective about whether this practice benefited our friendships and community. We were able to seek out and experience both socialization and solitude, unencumbered by the endless availability to others (via text or email), the distraction of numerous apps or tasks accessible from our phones, or expansive media consumption. We also knew we were risking being disconnected, forgetful, or uninformed. The real-life repercussions of our actions within a single week allowed us to weigh our choices more accurately, knowing the real trades-offs that are being made every time we choose to engage—or not—with the technology of our time.

The Endeavor Project can help us continue to explore and experiment with ways to build and maintain community and communal living. What do I hope to do with my new found space from technology? I would love to find ways to continue the Murchison experiment of shared meals, art, and resident-led space-making, and to create a communal kitchen. I hope to build adobe bricks and use them to make a small bridge from our garden, over the willow-draped arroyo, and into the juniper scrub brush. I see so clearly many hands in New Mexico sand, building something that cannot last as long as the ancients, but may outlast us all. I fully intend to milk the metaphor of bridge-building to its nourishing end. And finally, I hope to graduate with a meaningful job that feeds my passion lined up in Knoxville, Tennessee, so I can move near my sister and be a family in place again. Endeavor’s support makes it possible not just to imagine these projects, but to practice carrying them through, and to leave behind structures, material and relational, that invite others to continue.